Inverse Skip Strike Butterfly w/Puts

The strategy

You can think of this strategy as a back spread with puts with a twist. Instead of simply running a back spread with puts (sell one put, buy two puts), selling the extra put at strike A helps to reduce the overall cost to establish the trade.

Obviously, when running this strategy, you are expecting an enormous bearish move. So it’s a strategy for extremely volatile times when stocks are more likely to make wide moves in either direction.

When implied volatility rises, in general option prices go up independent of stock price movement. That’s why we need some help to pay for the strategy by selling the put at strike A, even though it sets a lower limit on your potential profit.

Ideally, you want to establish this strategy for a net credit whenever possible. That way, if you’re dead wrong and the stock makes a bullish move, you can still make a small profit. However, it may be necessary to establish it for a small net debit, depending on market conditions, days to expiration and the width between strike prices.

The further the strikes are apart, the easier it will be to establish the strategy for a credit. But as always, there’s a tradeoff. Increasing the distance between strike prices also increases your risk, because the stock will have to make a bigger move to the downside to avoid a loss.

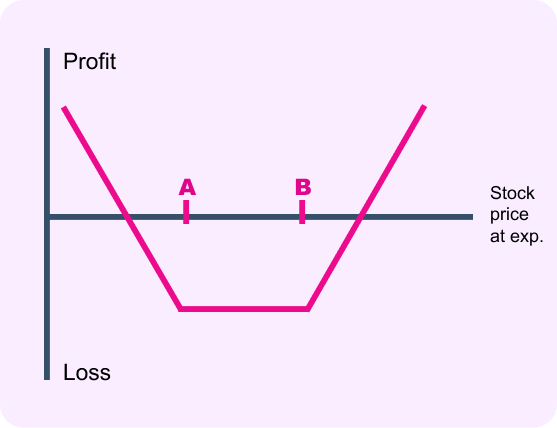

As with back spreads, the Profit + Loss graph for this strategy looks quite ugly at first glance. If the stock only makes a small move to the downside by expiration, you will suffer your maximum loss.

However, this is only the situation at expiration. When the strategy is first established, if the stock moves to strike C, this trade may actually be profitable in the short term if implied volatility increases. But if it hangs around strike C too long, time decay will start to hurt the position.

For this to be a profitable trade, you generally need the stock to continue making a bearish move down to or beyond strike A prior to expiration.