Diagonal Spread w/Puts

The setup

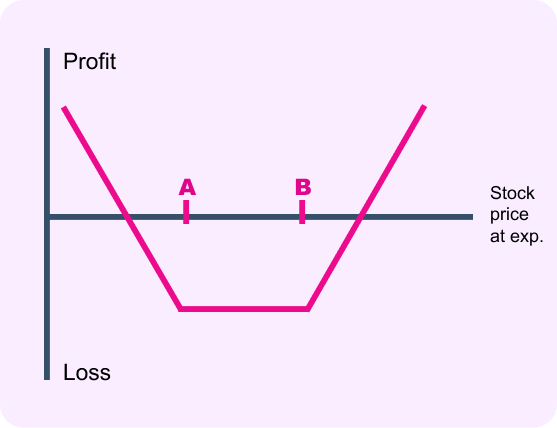

- Sell an out-of-the-money put, strike price B (near-term expiration – “front-month”)

- Buy a further out-of-the-money put, strike price A (with expiration one month later – “back-month”)

- At expiration of the front-month put, sell another put with strike B and the same expiration as the back-month put

- Generally, the stock will be above strike B

The strategy

You can think of this as a two-step strategy. It’s a cross between a long calendar spread with puts and a short put spread. It starts out as a time decay play. Then once you sell a second put with strike B (after front-month expiration), you have legged into a short put spread. Ideally, you will be able to establish this strategy for a net credit or for a small net debit.

For this Playbook, I’m using the example of one-month diagonal spreads. But please note, it is possible to use different time intervals. If you’re going to use more than a one-month interval between the front-month and back-month options, you need to understand the ins and outs of rolling an option position.

Options guys tips

Ideally, you want some initial volatility with some predictability. Some volatility is good, because the plan is to sell two options, and you want to get as much as possible for them. On the other hand, we want the stock price to remain relatively stable. That’s a bit of a paradox, and that’s why this strategy is for more advanced traders.

To run this strategy, you need to know how to manage the risk of early assignment on your short options.

Who should run it

Seasoned Veterans and higher

NOTE: The level of knowledge required for this trade is considerable, because you’re dealing with options that expire on different dates.

When to run it

You’re expecting neutral activity during the front month, then neutral to bullish activity during the back month.

Break-even at expiration

It is possible to approximate break-even points, but there are too many variables to give an exact formula.

Because there are two expiration dates for the options in a diagonal spread, a pricing model must be used to ’guesstimate‘ what the value of the back-month call will be when the front-month call expires. Most brokers that specialize in option trading have a Profit + Loss Calculator that may help you in this regard. But keep in mind, most Profit + Loss Calculators assume that all other variables, such as implied volatility, interest rates, etc., remain constant over the life of the trade — and they may not behave that way in reality.

The sweet spot

For step one, you want the stock price to stay at or around strike B until expiration of the front-month option. For step two, you’ll want the stock price to be above strike B when the back-month option expires.

Maximum potential profit

Profit is limited to the net credit received for selling bothputs with strike B, minus the premium paid for the putwith strike A.

NOTE: You can’t precisely calculate potential profit at initiation, because it depends on the premium received for the sale of the second put at a later date.

Maximum potential loss

If established for a net credit, risk is limited to the difference between strike A and strike B, minus the net credit received.

If established for a net debit, risk is limited to the difference between strike A and strike B, plus the net debit paid.

NOTE: You can’t precisely calculate your risk at initiation,because it depends on the premium received for the sale of the second put at a later date.

Margin requirement

Margin requirement is the difference between the strike prices (if the position is closed at expiration of the front-month option).

NOTE: If established for a net credit, the proceeds may be applied to the initial margin requirement.

Keep in mind this requirement is on a per-unit basis. So don’t forget to multiply by the total number of units when you’re doing the math.

As time goes by

For this strategy, before front-month expiration, time decay is your friend, since the shorter-term put will lose time value faster than the longer-term put. After closing the front-month put with strike B and selling another put with strike B that has the same expiration as the back-month put with strike A, time decay is somewhat neutral. That’s because you’ll see erosion in the value of both the option you sold (good) and the option you bought (bad).

Implied volatility

After the strategy is established, although you want neutral movement on the stock if it’s at or above strike B, you’re better off if implied volatility increases close to front-month expiration. That way, you will receive a higher premium for selling another put at strike B.

After front-month expiration, you have legged into a short put spread. So the effect of implied volatility depends on where the stock is relative to your strike prices.

If your forecast was correct and the stock price is approaching or below strike A, you want implied volatility to decrease. That’s because it will decrease the value of both options, and ideally you want them to expire worthless.

If your forecast was correct and the stock price is approaching or above strike B, you want implied volatility to decrease. That’s because it will decrease the value of both options, and ideally you want them to expire worthless.

If your forecast was incorrect and the stock price is approaching or below strike A, you want implied volatility to increase for two reasons. First, it will increase the value of the near-the-money option you bought faster than the in-the-money option you sold, thereby decreasing the overall value of the spread. Second, it reflects an increased probability of a price swing (which will hopefully be to the upside).